library(knitr)

library(plotrix)

library(dots)

library(scales)

library(plyr)

library(smacof)Strategic consensus mapping

Calculations of a paper by Tarakci et al. (2014) replicated in R.

In this script I try to reproduce the Strategic Consensus Mapping (SCM) method as outlined by Tarakci et al. (2014) in R. SCM is a combination of four methods or defined measures:

- The vector model of unfolding to visualize respondents preferences

- A standardized measure of within-group consensus

- A measure of between-group similarity

- Multidimensional scaling to visualize between-group similarity

Data

x <- read.csv2("data/tmt.csv")

kable(x)| Priority | TMT1 | TMT2 | TMT3 | TMT4 | TMT5 | TMT6 | TMT7 | TMT8 | TMT9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Safety | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 6 | 4 | 7 | 5 |

| Certification | 4 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 7 |

| Expert Staff | 7 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 4 | 7 | 3 | 6 |

| Regulation | 6 | 7 | 5 | 6 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| Reliable Network | 5 | 3 | 6 | 5 | 3 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 3 |

| Organizational Structure | 3 | 5 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 4 |

| Innovativeness | 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 1 |

H <- x[, -1]

rownames(H) <- x[, 1]Vector model of unfolding

The vector model of unfolding is used to geometrically visualize each respondents preference order of the strategic items.

#http://math.stackexchange.com/questions/180418/calculate-rotation-matrix-to-align-vector-a-to-vector-b-in-3d/897677#897677

matrix_to_rotate_x_on_y <- function(x,y)

{

x <- x / sum(x^2)^.5

y <- y / sum(y^2)^.5

matrix(c(x[1]*y[1] + x[2]*y[2], x[1]*y[2] - x[2]*y[1],

-(x[1]*y[2] - x[2]*y[1]), x[1]*y[1] + x[2]*y[2]), 2, by=T)

}

vmu <- function(H, reflect=c(F,F))

{

n <- nrow(H) # n x m matrix

m <- nrow(H)

H <- scale(H) * (n/(n-1))^.5 # scale with n not n-1

dec <- svd(H)

U <- dec$u

V <- dec$v

r <- length(dec$d)

D <- diag(dec$d, r, r)

R <- diag( ifelse(reflect == 0, 1, -1) )

l <- m^.5 # lambda scaling of decompsoition

X <- l * U # no singular values assigned to row points

A <- l^-1 * V %*% D # makes each squared rowsums equal to one

X <- X[, 1:2] %*% R # get first two principal components and

A <- A[, 1:2] %*% R # flip axes if prompted

rownames(X) <- rownames(H)

rownames(A) <- colnames(H)

am <- colMeans(A) # average loading vector

alpha <- (sum(am^2))^.5 # calculate alpha measure using unrotated

# solution, p. 1059

Q <- matrix_to_rotate_x_on_y(am, c(1,0)) # rotate plot so am corresponds

XQ <- X %*% Q # with x-axis

AQ <- A %*% Q

list(H=H, # original input (high preference = low value)

X=X, # matrix of row points

A=A, # matrix of column vectors

XQ=XQ, # matrix of row points after rotation on average column vector

AQ=AQ, # matrix of column vectors after rotation

a=am, # average column vector

alpha=alpha) # measure of within-group consensus

}

# function for textboxes (uses dots and plotrix package)

textbox2_ <- function(x,y, label, ...)

{

w <- dots::formal_call("strwidth", s=label, ...) / 2 * 1.1

plotrix::textbox(c(x - w, x + w), y, label, justify="c", ...)

#formal_call("textbox", x=c(x - w, x + w), y=y,

# textlist=label, justify="c", ...)

}

textbox2 <- Vectorize(textbox2_)

plot_vmu <- function(v, prop=.9, rows=TRUE, columns=TRUE,

average=TRUE, circle=TRUE, frame=FALSE)

{

X <- v$XQ

A <- v$AQ

# rescale X to fit within unit circle. This destroys projection property but

# not important as no axis calibration is used in plot

X <- X / max(rowSums(X^2)^.5) # scale X to fit within unit circle

X <- X * prop # make a bit smaller than uni circle

# set up plot

mx <- 1.1 #max(max(abs(X)), max(abs(A))) # max value to set plot limits

op <- par(mar=c(.5,.5,.5,.5))

plot(NULL, xlim=c(-mx, mx), ylim=c(-mx, mx), asp=1,

xaxt="n", yaxt="n", xaxs="i", yaxs="i", xlab="", ylab="",

frame=frame)

if (circle) {

draw.circle(0,0,1, col = grey(.97))

}

segments(-1, 0, 1, 0, col="grey")

segments(0, -1, 0, 1, col="grey")

# respondents (variables)

if (columns) {

segments(0,0,A[,1],A[,2], col="blue", lwd=2)

points(A, col="#0000FF90", pch=15)

pos <- ifelse(A[,1] > 0, 4, 2) # position labels by hemisphere

text(A, labels=rownames(A),cex=.7, pos=pos, col="blue")

}

# row objects

if (rows) {

points(X, pch=18, col="#FF000090", cex=1.5)

text(X, labels=rownames(X), col="red", cex=.7, pos=3)

#textbox2(X[, 1], X[, 2], label=rownames(X),

# col="red", cex=.7)

}

# average of all vectors ( ~ prototypical respondent)

am <- colMeans(A[, 1:2])

if (average) {

#segments(0,0, am[1], am[2], lwd=2)

arrows(0,0,am[1], am[2], lwd=2, length = .1)

}

# the squared row sums of A are one, so 1 is maximal length of average

par(op)

}The following graphic is a reproduction of Figure 1 (p. 1058). The scaling of the objects might differ to the one in the paper. This will hoewever not affect interpretation of the solution, as the respondents axis are not calibrated using tick marks. Also, we chose to draw a unit circle, to indicate the longest possible vector.

v <- vmu(H)

plot_vmu(v)

To read off the approximated preference order of each strategic items for a respondent, the items are orthogonally projected on the respondent’s axis.

add_axes <- function(A, col="#0000FF50", lwd=2, lty=5)

{

if (!is.matrix(A)) # convert if a vector

A <- matrix(A, ncol=2, by=T)

A <- t(apply(A, 1, function(x) x / sum(x^2)^.5 ))

segments(-A[ ,1], -A[ ,2], 0, 0, lty=lty, col=col, lwd=lwd)

}

add_projections <- function(v, i=NULL, j=NULL)

{

X <- v$XQ

A <- v$AQ

if (is.null(i))

i <- 1L:nrow(X)

if (is.null(j))

j <- 1L:nrow(A)

X <- X / max(rowSums(X^2)^.5) * .9 # scale X to fit within unit circle

# draw respondent axes

add_axes(A[j, ], col="#0000FF50")

# draw projections of row points on respondent axes

Xs <- X[i, , drop=FALSE] # select points to project

for (jj in j) {

a <- A[jj, ] # current axis to project on

P <- a %*% t(a) / as.numeric(t(a) %*% a) # projection matrix

Ps <- Xs %*% P # project all points

segments(Xs[,1], Xs[,2], Ps[,1], Ps[,2], lty=2)

}

}plot_vmu(v)

add_projections(v, j=1)

# preference orders reproduced by projected order

preferences <- function(v, j=NULL)

{

H <- v$H

R <- v$H

R[ , ] <- NA

X <- v$XQ

A <- v$AQ

if (is.null(j))

j <- 1L:nrow(A)

for (jj in 1L:nrow(A)) {

a <- v$AQ[jj, ] # current axis to project on

P <- a %*% t(a) / as.numeric(t(a) %*% a) # projection matrix for axis j

Xp <- X %*% P # projections (not scaled like plot)

d <- svd(Xp) # projection coords in PCA space

pc1 <- d$u[, 1] * d$d[1] # coords on first PC in PCA system

v1 <- d$v[, 1] # 1st right singular vector, i.e. direction of PC1

an <- a / sum(a^2)^.5 # a to length 1

if (t(v1) %*% an < 0) # Reflect coords if PC does not match

pc1 <- pc1 * -1 # direction of respondent vector

R[ , jj] <- rank(pc1) # order(order(pc1)) # to avoid bindings

}

rownames(R) <- rownames(H)

R[ , j, drop=FALSE]

}The reproduced preference order for respondent 7 is slightly different from the original one. The following table compares the two orders and shows the absolute differences for the rank.

j <- 7

pref <- preferences(v, j=j)

pp <- cbind(H[, j], pref, abs(H[, j] - pref))

colnames(pp) <- c("original", "reproduced", "delta")

pp original reproduced delta

Safety 4 4 0

Certification 5 6 1

Expert Staff 7 7 0

Regulation 3 3 0

Reliable Network 6 5 1

Organizational Structure 1 2 1

Innovativeness 2 1 1Some preference orders are better reproduced than others. The following table shows the deltas in rank order for all respondents. The order for respondent 1 is reproduced perfectly in the plot while the reproduction for the order of respüondent 8 is the worst. This could also be expected from inspecting the length of respondent8’s vector, as it is shorter than the others.

abs(H - preferences(v)) TMT1 TMT2 TMT3 TMT4 TMT5 TMT6 TMT7 TMT8 TMT9

Safety 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 1

Certification 0 1 0 1 1 2 1 4 1

Expert Staff 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 1 1

Regulation 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 0

Reliable Network 0 0 0 0 1 3 1 3 2

Organizational Structure 0 0 1 1 1 0 1 0 1

Innovativeness 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 0 0A measure of consensus for each group

The authors suggest a measure of within-group consensus. It builds upon the length of the vector of the average repondent. It is defined as

(p. 1059) with

As the vectors for all respondents have a maximum length of one (i.e. when they touch the unit circle) also the average respondent vector has a maximal length of one. This is the case when all respondent’s vectors point into the same direction. It will be near to zero, if all respondents vectors point into different directions. For our example the value is 0.55.

A measure of between-group similarity

Besides an inter-group consensus measure the authors supply a measure to compare the similarity of the preference judgements across groups. They suggest to use the scores of the strategy items on the first principal compenent of te rotated solution. The direction of the PC is the same as the direction of the protoypical group member. In other words, the PC values reflect the order of the items for the prototypical group member.

# create random data

random_preferences <- function()

{

}

set.seed(0)

rnames <- rownames(H)

l <- replicate(9, apply(H, 2, sample), simplify = FALSE) # permute data

l <- lapply(l, function(x) {

x <- x[, 1:sample(5:9, 1)] # change size

rownames(x) <- rnames # add rownames

x

})

vmus <- lapply(l, vmu)

op <- par(mfrow=c(3,3))

dummy <- lapply(vmus, plot_vmu)

par(op)vv <- c(list(v), vmus) # add first VMU result to list

proximities <- function(l)

{

d <- plyr::ldply(vv, function(x) x$XQ[, 1]) # matrix of PC1 coords

S <- cor(t(d)) # similarity matrix

D <- 1 - S # dissimilarity matrix

list(S=S, D=D)

}

# overall measure of inter-group similarity

r_overall <- function(S)

{

rs <- S[upper.tri(S)]

sqrt(mean(rs^2))

}

p <- proximities(vv)For our random data the overall measure for inter-group similarity is 0.46.

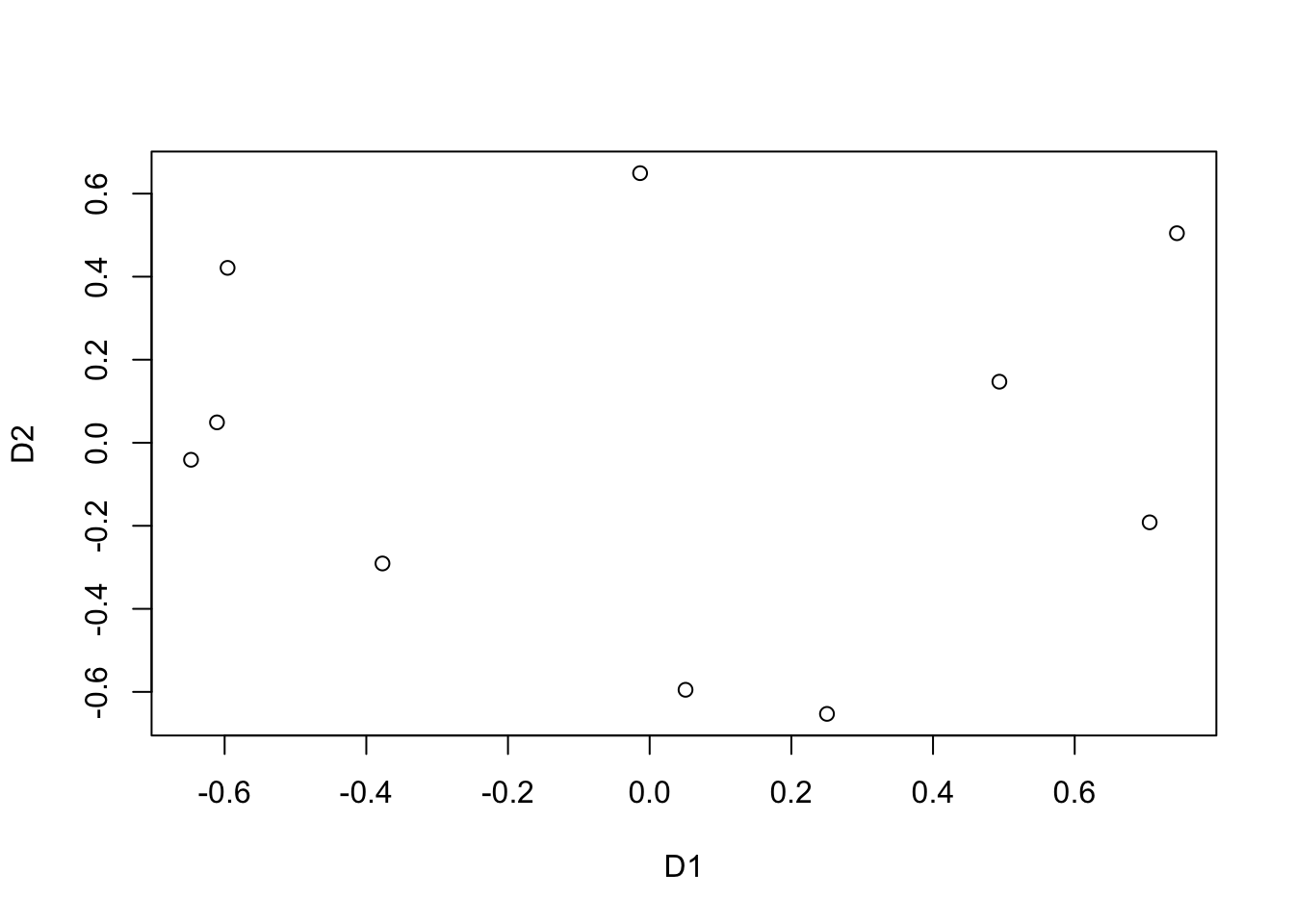

Multidimensional scaling to visualize between-group similarity

The last step is to visualize the preference similarities between groups. Herefore the authors apply MDS to the dissimilarity matrix.

res <- smacof::smacofSym(p$D, ndim=2, type="interval")

C <- res$conf

plot(C)

# between group similariry correlation matrix (Appendix p.1069).

deps <- c("TMT", "Strategy", "HR", "Sales", "Operations",

"Finance", "IT", "Business Development", "Communication", "Safety")

tri <- c(

1.00,

0.72, 1.00,

0.71, 0.78, 1.00,

0.86, 0.96, 0.81, 1.00,

0.41, 0.74, 0.84, 0.62, 1.00,

0.74, 0.82, 0.88, 0.80, 0.82, 1.00,

0.79, 0.91, 0.95, 0.94, 0.76, 0.85, 1.00,

-0.03, 0.33, 0.58, 0.27, 0.60, 0.30, 0.46, 1.00,

0.77, 0.88, 0.95, 0.87, 0.87, 0.96, 0.94, 0.40, 1.00,

0.86, 0.71, 0.87, 0.78, 0.72, 0.90, 0.81, 0.31, 0.91, 1.00)

n <- length(deps)

U <- matrix(NA, n, n)

U[upper.tri(U, diag = T)] <- tri

R <- t(U)

R[upper.tri(R)] <- U[upper.tri(U)]

D <- 1 - R

colnames(D) <- deps

rownames(D) <- depsres <- smacof::smacofSym(D, ndim=2, type="interval")

C <- res$conf

plot(C, asp=1)

text(C, labels=deps)

# isocontour lines

g <- 1

# calc euclidean distances to group

xy <- C[g, ]

G <- sweep(C, 2, xy, "-")

e <- rowSums(G^2)^.5 # euclidean distances to points from point g

rs <- p$D[ , 1] # 1 - rs

d <- data.frame(r=rs[-g], e=e[-g])

m <- lm(e ~ r, data=d)

m$residuals Strategy HR Sales

-0.1656422 0.2908816 -0.2739035

Operations Finance IT

0.2904309 -0.2536563 -0.2171280

Business Development Communication Safety

1.2529371 -0.3534333 -0.5704864 # group to centerLiterature

- Tarakci, M., Ates, N. Y., Porck, J. P., van Knippenberg, D., Groenen, P. J. F., & de Haas, M. (2014). Strategic consensus mapping: A new method for testing and visualizing strategic consensus within and between teams. Strategic Management Journal, 35(7), 1053–1069. doi:10.1002/smj.2151

Todo

the component loadings in A are the correlations between the object scores for each strategy item and the respondents’ answers.

library(pmr)

#cor(H[, 1], X[1, ])

# rotation

## create an artificial dataset

X1 <- c(1,1,2,2,3,3)

X2 <- c(2,3,1,3,1,2)

X3 <- c(3,2,3,1,2,1)

X4 <- c(1,1,3,3,2,2)

n <- c(6,5,4,3,2,1)

test <- data.frame(X1,X2,X3,X4, n)

## multidimensional preference analysis of the artificial dataset

d <- mdpref(test,rank.vector=F, 2)

abline(v=0, h=0, col="grey")

A <- d$ranking[, 6:7]

segments(0,0, A[,1], A[,2])